It’s not that the phrase “Asian Steampunk” is intrinsically flawed. It’s just that the range of concepts displayed in “Asian Steampunk,” whether fiction, gaming, or costumes, are so so… limited. You’d never catch “Western Steampunk” limiting itself to cowboys, hard-boiled detectives, and British bobbies. Why then limit yourself to samurai, ninja, and geisha? There was so much more to the cultures and peoples of east Asia than that.

Ultimately the problem springs from some basic misconceptions. Steampunk uses archetypes of real life and popular fiction from the 19th century, but the archetypes drawn upon for “Asian Steampunk” are unimaginative and display little knowledge of the intriguing mix of tradition and modernity which so many of the east Asian peoples had during the late 19th century.

Consider some of the real life (and real fictional) Asian figures of the steampunk era:

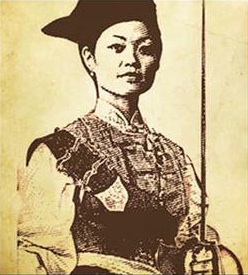

- Zeppelin pirates are a staple of steampunk, but nautical pirates were a reality in the waters of Southeast Asia. Notable among these were the female pirates, from Zheng Yi Sao and Cai Qian in the beginning of the 19th century to Lo Hon Cho and Lai Choi San in the early part of the 20th century. These women were captains and admirals, commanding dozens of ships and leading them into battle from the front, gaining reputations as fierce fighters. According to a contemporary Chinese account Cai Qian Ma even commanded ships with crews of niangzijun, “women warriors.”

- One of the archetypal steampunk figures is Jules Verne’s Captain Nemo. While there was no real-life analogue for Nemo, one fictional figure who was similarly archetypal in Japanese popular literature during the early 1900s was Oshikawa Shunro’s Captain Sakuragi, who appeared in six novels from 1900 to 1907. Sakuragi is a Japanese naval officer who grows disgusted with the Japanese government’s inability to do anything to resist the imperialism of Western governments in Asia and Japan. Sakuragi quits the Navy and on an isolated island somewhere in the Indian Ocean builds the Denkotei, an “undersea battleship” armed with futuristic weapons, including torpedoes and high explosive shells. In the novels the Denk0tei demolishes white pirates, the Russian, British, and French fleets, and Sakuragi and his crew go ashore to help Filipino “freedom fighters” against the imperialistic American occupiers.

- Much of the appeal of zeppelins and other steampunk vehicles is the mobility they offer, especially when compared to the limited mobility most people had in the steampunk era. The popular image of east Asians is of people who did not travel much. But, to take just one example, in the latter half of the 19th century there were dozens of Chinese junks working coastal Californian waters and serving the many Chinese fishing villages along the central California coast, and in the first half of the 20th century there were a large number of Japanese-piloted sampans fishing the waters around Hawaii. Any of these individuals could easily be reinterpreted in a steampunk fashion.

- The hardboiled, crime-solving reporter was a part of Western mystery fiction from the 1880s, but in real life there were large numbers of reporters just like that in China, especially Shanghai, where the competition between newspapers was intense and reporters and editors did anything they could for a hot scoop. These newspapers were modeled on American and English newspapers, and though many of them were aimed at the Europeans in China, some were written by Chinese for Chinese.

- Roguish treasure-hunters need not automatically be white. Since the 11th century there has been a tradition among Nyingma Buddhists in Bhutan and Tibet of a special class of lamas, the gter-ston or “treasure hunters,” who “discover” gter-ma (scriptural treasures) which have supposedly been hidden away during the Buddha’s lifetime so that they can be found and revealed to the world at a foreordained time. The gter-ston were active through the 19th century, and while some were genuine many were fraudulent.

- From the mid-17th century through the 1920s Chinese novels translated into Mongolian were in huge demand in Mongolia, and there was a flourishing trade in them. But the problem for the Mongolian bookbuyers and booksellers was not only the bidding wars which would break out with Russian, Mongolian, and Chinese buyers, but that getting the manuscripts back to Mongolia to sell was difficult because of the very real chance that those transporting the books would be attacked on the way back by bandits wanting to get the manuscripts and sell them for themselves. This resulted in decades of adventurous Mongolian book traders as skilled with sword and gun as they were at selling books.

- In 1905, following the Japanese victory over Russia in the Russo-Japanese War, many Indians saw the triumph of Japan as both inspiration (Gandhi urged South African Indians to “emulate the example of Japan”) and as an indication of how far India had fallen. Several Indians decided that what India need was to imitate Japanese ways, so these men and women (one of whom was a “political dacoit”) opened martial arts academies, especially in Calcutta, and taught Bengali youth “how to use the staff, the fist, the sword, and the gun” for revolutionary and political purposes. A number of these students went on to open their own martial arts schools.

- From at least the 1850s, numerous Asian men and women were employed as freelance spies across Asia. Their employers were occasionally Western and Eastern countries but more often Western and Eastern companies; in the words of the Singapore Straits Times in 1905, “The enormous profits which can be made by those who promote combines, railway amalgamations, mineral or other State concessions make it worth the while of capitalists to scatter some thousands of pounds amongst well-dressed and well-educated ladies and gentlemen of leisure who will exert themselves to obtain accurate information from authentic sources as to coming events of financial significance.”

- Lastly, while fictional crime-solvers, from consulting detectives to the police, are generally thought of as primarily Western, in real life during the steampunk era they were widespread in east Asia. In India, the police employed policewomen in the Punjab in 1875, and women worked as private detectives in Calcutta by 1911. In Japan, the Iwai Private Detective Agency opened in 1886 and lasted through the 1920s. A similar agency was active in Singapore in 1909. In Thailand in the early 1900s, the enthusiasm of Prince Vajiravudh (later King Rama VI) for private detective fiction resulted in a series of 15 stories about Th0ng-in, a Thai combination of Sherlock Holmes and Auguste Dupin; these stories resulted in a number of Thai men and women opening their own private detective agencies. The very popular San Shà detective stories by Shwe Ú-daùng had a similar effect in Burma in the 1920s.

Pirates, submarine captains, hard-boiled reporters, female private detectives… these are all part of east Asian history and popular culture in the steampunk era. Steampunk writers and cosplayers, expand your horizons!

Jess Nevins is the author of the World Fantasy Award-nominated Encyclopedia of Fantastic Victoriana, other works on Victoriana and pulp fiction, and a collection of extensive comic book annotations, inlcuding The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen.